Gomti nadi update - Restoration of the Gomti Riverfront in Lucknow : Claude Martin’s Legacy

- By

- Dr Amita Sinha

- September-07-2018

The 18th-century French adventurer Claude Martin left an

extraordinary architectural legacy in Lucknow, the city of the Nawabs. Many

buildings attributed to him are sited on the banks of the Gomti, designed to

take advantage of the river's views and cooling effect. They represent an

eclectic mix of indigenous Nawabi and Palladio-inspired detailing, striving for

scenic effects, especially on the riverfront. Widely emulated by the rulers and

nobility of Lucknow, they defined the hybrid style for which the city became

famous. The Avadh Nawabs had continued the riverfront building tradition of the

Mughals, but Martin's design genius coupled with his European sensibility gave

a new twist to their practice. Lucknow's cultural climate of assimilation, the

indulgent attitude of the Nawabs who were great patrons of art and

architecture, their fascination with the exotic, and Martin's wealth no doubt

facilitated this experimentation. Martin's inventive genius amalgamated diverse

influences from Indian and European sources and wove them into something new

and unprecedented. Lucknow's architectural heritage - comprising buildings

designed in the hybrid style in a cultural landscape of riverfront architecture

that was responsive to climate and terrain - is richer for that (figures 1 and

2).

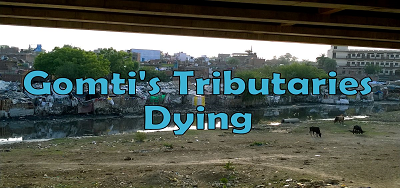

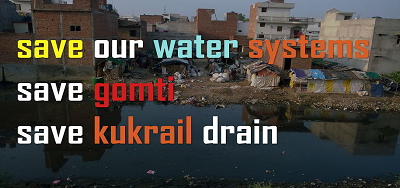

Figure 1

Figure 2 – The Gomti Riverfront today

The city turned its back on the Gomti with the passing of

time and changing political and economic circumstances in the 20th century,

which also saw the confinement of the river within embankments and the loss of

its floodplain. The consequences of forgetting this old tradition of building

with the river, not against it, are dire. In restoring Martin's buildings,

their relationship with the site and with the Gomti should be reconstructed,

thereby preserving their historic integrity. This would entail the development

of public open space along the river, providing an opportunity to see and enter

the historic monuments from the Gomti as they were originally meant to be seen

and accessed.

Claude Martin

Rosie Llewellyn-Jones' scholarship has rehabilitated

Lucknow's so-called "bastard" architecture, much reviled because of

its eclectic mix of European and Indian styles. Her biography of Claude Martin

has posthumously repaired his reputation as well (figure 3). Martin, who had

served in both French and English East India Companies, made his fortune in

Lucknow as Superintendent of the Avadh Nawabs arsenal. He owned land and many

buildings that he rented to the Nawabs, loaned money at exorbitant rates, and

cultivated powerful Company officials. He left his considerable fortune for

educating children of all faiths in Lucknow, Calcutta, and Lyon; to the

indigent; and for rehabilitating convicted prisoners. His life reads as a Robin

Hood tale of "robbing” the rich to aid the poor, and he, more than any

other white nabob in India, gave back to the country he had made his fortune

in.

Figure 3 – Bust of Claude Martin (1736-1800) in La

Martiniere College, Lucknow

Martin's eclectic interests in architecture and the arts

were those of a polymath, one who imbibed influences from diverse sources.

Mughal architecture, especially riverinc pavilions and tomb structures, was to

have a profound, although unacknowledged, influence on him. Martin's buildings

reflected the tastes of a renaissance man, one who was not only an amateur

architect but had expertise in casting cannon and floating air balloons, and

tinkered with steam engines and other mechanical gadgets, earning him the title

of "a very ingenious man". His collection of paintings, his extensive

Library, and his ecumenical philanthropy were a testament to European

enlightenment values. He was an adventurer and risk-taker, and above all

curious - qualities that made him open to diverse influences including those

from the country where he arrived in 1751 at the age of 15, and where he lived

for half a century until the end of his life in 1800.

Farhat Baksh, Constantia and Barowen

Nawabi country houses and palaces, heavily influenced by

Martin's buildings, are now celebrated as examples of an exuberant and whimsical

hybrid style. Critical reviews have however concentrated upon the European

features of Martin's architecture, in particular their design as stand-alone

buildings with handsome exteriors, displaying Greco-Roman influence in their

pediments, columns, statuary and crenellations.

Martin's status as an amateur architect gave him the

freedom to experiment and not be confined by any canon. The facade elements

show his eclectic taste in architecture, presumably developed from the study of

volumes on Etruscan, Egyptian and Palladian designs in his vast library. His

own houses, Lakh-e-pera (later renamed Farhat Baksh) and Constantia, are

singular in their defensive character, with moat, drawbridge, towers and iron

doors with heavy bolts.

Martin owned land within and outside Lucknow (and in

other places such as Najafgarh and Kanpur where he practiced indigo farming)

and as many as 13 buildings. It is not clear how many buildings he designed

himself - they are likely Hyat Baksh, Asafi Kothi, Bibiapur, Barowen and his

own houses - Farhat Baksh and Constantia. Although all buildings were located

in proximity to the Gomti, Farhat Baksh, Constantia and Barowen had an intimate

relationship with the river. Farhat Baksh was built on the Gomti itself, about

one-fifth into its width, and the other two buildings responded to the river

directly. The three structures were not alike but shared a sensitivity to the

landscape, distinguishing them from other country houses in Lucknow. Of the

three, only Farhat Baksh and Constantia are extant while the ruins of Barowen

invite an imaginative reconstruction through landscape restoration.

The buildings have been discussed at length in

19th-century European travelogues as well as in recent scholarship on Lucknow

buildings. Farhat Baksh and Constantia were objects of curiosity and wonder, as

well as of amusement and revulsion, especially the latter. They have striking

silhouettes, reflected in the waters below. The triangular pediment, festoon

swags around octagonal towers, composite order pilasters and the mock venetian

blinds in octagonal cartouches and windows give Farhat Baksh a distinctly

European look. Constantia's facade went even further in looking spectacular

lions with burning torches lighting up their eyes, sphinxes, statues of shepherdesses

and Chinese mandarins, flying quadrant arches, battlement towers and flagstaff,

Barowen, constructed in 1803-04 by Nawab Saadat Ali Khan, based upon Martin's

design, had a handsome three-storey circular portico, octagonal look-out

towers, kiosks with oval openings and rounded arched openings with stucco

friezes imitating sun-burst.

Llewellyn-Jones observes that European influence liberated the exterior street facades of Nawabi buildings - they were no longer blank walls screening the interior from prying eyes. Yet the visual relationship between Nawabi palaces and the river, following the Mughal precedent, had always existed. Views to the river, as well as the views from the river, were important, as evident in numerous paintings by European and Indian artists. These landscape views where buildings were displayed to their greatest visual advantage depict a cultural landscape fashioned out of the interface of land and water. The riverfront facade of Martin's buildings contributed to that tradition. Constantia beckoned the traveler on the river - conjuring up the romantic image of the lighthouse guiding a lost ship, tossed on the waters on a stormy night (figure 4).

Figure 4 – Costantia, watercolour by Sitaram (1814)

Martin's European-looking flourishes - facades animated

with statuary, look-out towers, lighthouse - masked a significant borrowing

from climate-responsive Indian building traditions. Farhat Baksh was designed

for an intimate visual and tactile encounter

with the Gomti (figure 5). Martin literally lived in and on the river. The two

lower storeys, built like grottoes where Martin resided in the hot summers,

ascending as the river rose, drew upon the taikhanas (underground rooms) and

baolis (step-wells) of northern Indian architecture. The third (ground floor)

and fourth (first floor) storeys of Farhat Baksh overlooking the river at its

height were similar to Mughal pavilions on the Yamuna, where panoramic views

and cool breezes were enjoyed.

Figure 5 – Farhat Baksh and Chattar Manzil

Constantia too had subterranean rooms that Martin would

have inhabited in summers had he lived long enough to occupy the building. In

one of them instead lies his tomb, less than a metre above ground in the Muslim

fashion. The plan of the central part of Constantia bears a close resemblance

to the Mughal emperor Humayun's tomb in Delhi, with smaller octagonal rooms

leading off from the large space in the centre. Constantia, Martin's final

resting place, continues the great tomb-building tradition of Muslim rulers in

the Indian subcontinent. Like the Taj Mahal's wells in the basement sunk into

the Yamuna bed to protect the mausoleum from floods, Constantia's four circular

wells were dug about 6 metres below the water level to provide drainage, and

culminated in octagonal towers at the top of the building. Pottery ducts set

into their walls drew in hot air and released it through eight roof funnels, as

in many Nawabi buildings.

Musa Bagh (the colloquial version of Monsieur Bagh) on

the outskirts of Lucknow was initially a walled Nawabi charbagh laid out by

Nawab Asaf-ud-daulah. In 1803 04, Barowen, based on Claude Martin's design, was

built by his half-brother Nawab Saadat Ali Khan overlooking the garden. It was

a country house used for entertaining guests and for watching stag fights on

the far bank of the Gomti less than 300 metres away. Barowen was ingeniously

designed, attesting to its creator's rich imagination. The handsome

European-looking three-storey riverfront facade led to the building interior

built into an artificial hill. The large sunken courtyard surrounded by small rooms

and verandahs at the two-storey back of the house, was cooled by the earth

around the structure, while the front was cooled by river breezes. The sunny

front portion of the house was lived in during the winter while the rear part

was a summer residence. No descent was required into the sunken courtyard - the

floor in the house was the same level throughout. Kiosks with spiral steps at

the far rear corners of the building led to a large charbagh outside, recalling

Mughal gardens on the leeward side of the raised riverfront terraces with airy

pavilions on the Yamuna. The large requirements of the royal household, as at

other country houses, were met not through a horizontal arrangement of spaces

but by a vertical stacking of rooms. Llewellyn-Jones calls this building a

"perfect synthesis of a European house in the grand tradition with the

practical Indian traditions of a large open courtyard surrounded on three sides

by small rooms”.

The last battle of the Uprising took place in Musa Bagh.

Begum Hazrat Mahal, leader of rebel forces, had made the site her headquarters

and stationed there a force of 9,000 men. On March 19, 1858, the final and

decisive battle took place when the two-pronged attack by Company forces caused

the rebels to retreat from Lucknow (figure 6).

Figure 6 – Musa Bagh Lithograph

The building was damaged but still standing, as an 1858

photograph shows. However very little of the building now remains and the

garden too is lost to farming. The ruins preserved in the flat plain are

striking (figure 7).

Figure 7 – Ruins of Musa Bagh

A small building north of the ruins contains the mazar

(tomb) of Syed Imam Ali. Here melas are held on Jumeraat (new moon) and on

Vasant Panchami (spring equinox). West of the ruins is the cemetery of Captain

Swale, of the Sikh Irregular Cavalry, killed in action in the final battle of the

Uprising. Every Christmas, a mela is held in honour of "Captain

Sahib". A village of 500 residents lies south of Musa Bagh and within and

surrounding the site are wheat, lentil and mustard fields. A variety of open

space types - forests, urban parks, and institutional campus - exist within a

0.8-kilometre radius while the Gomti, hidden by embankments, flows about 1.2

kilometres away (figure 8).

Figure 8 – Landuse around Musa Bagh

Musa Bagh Restoration and Gomti Remediation

Historic preservation presents an opportunity to restore

the lost relationship between the building and the landscape. This is

especially truc of Martin's buildings in Lucknow, designed as they were with

the river in mind. The buildings and their gardens are memorials not only to

Claude Martin's ingenuity but also to cataclysmic events in Lucknow's fractured

history. Restoring the site is essential for preserving the historic integrity

of the building, and can also lead to larger-scale remediation of the Gomti

riverfront. The river's containment within the levees has caused the

disappearance of wetlands - ecosystems crucial for accommodating the overflow

in the monsoons. As Lucknow expands with few if any development regulations,

its sprawl, especially on the Gomti floodplain, has severe environmental

consequences. About 12.8 per cent of the urban development of Lucknow has

occurred on the Gomti floodplain. It is imperative that the floodplain ecology

be not further disturbed and any new development have minimal impact. Wetlands

and lakes have also been encroached upon, leading to frequent flooding in the

low-lying residential areas of Lucknow. Historically the city had several

"tals” or ox-bow lakes created from cut-off meanders of the river as it

changed its course. These retained water during the dry periods, reduced flood

levels and most importantly sustained biodiversity by providing feeding and

breeding areas for birds and fishes. Their slow disappearance has been

alarming, leading to a public campaign for restoring the river by 2020. Outside

the densely built areas of the city, riverfront conservation zones, where

natural habitats for fauna are protected from further urban development, should

be designated.

Landscape restoration of Martin's building sites can be

part of a larger planning of the Gomti riverfront as a cultural and

environmental heritage corridor. Musa Bagh is on the outskirts of the city. In

the past it was accessed from the river as well as the old brick road from

Lucknow. Presently the Ring Road connects the city to the site; it has also

brought new housing development in its wake. Farms have given way to colonies

built by the State Housing Board and private developers. The Gomti today is not

physically and visually accessible from Musa Bagh. To encourage heritage

tourism along the Gomci riverfront in Lucknow, Musa Bagh, as other heritage

sites in the historic city, should be entered from the river (figure 9). The

historic connection between the ruins and the Gomti can be re-established by

removing the embankment and allowing the choked river to breathe and flood

naturally. In the landscape reclamation proposal developed by this writer and

her students, the Gomci is rechannelled, shortening its course and creating an

ox-bow lake. The land between Musa Bagh and the river is regraded into three

terraced wetlands that will be flooded incrementally as the river rises during

monsoons. The extensive wetlands will function as a sanctuary for birds that have

lost their habitat due to urbanization along the Gomti.

Figure 9 – Heritage Trail along the Gomti Riverfront

Musa Bagh Memorial Park forms the core of a larger

landscape conservation zone Created to protect green open spaces from urban

encroachment. The area on the north and west, where farm fields are being

cleared for housing, will be planted with mango and lychee orchards to provide

a buffer area around the Park. The existing protected forest will be connected

to the Memorial Park and proposed orchards with a trail system. A maidan is

proposed at the northern entry to the Park where fairs are held at the tombs,

and a large retention pond can be constructed to irrigate the orchards. Thus

the Musa Bagh Memorial Park can be the core of a 423-hectare conservation zone

for increasing greenery and wetlands on the Gomti floodplain (figure 10).

Figure 10 – Musa Bagh conservation zone

The Nawabi garden at the back of Barowen lies buried

under tilled farmland, although the outlines of garden plots are still visible

in satellite images, awaiting surface excavation that will reveal the garden

remnants. The satellite image shows lines that were likely pathways running

through the length and breadth of the 10.6-hectare site, hinting at possible

charbagh layouts. Our proposal for the Nawabi garden is a four-square charbagh

with a large central pool and four water channels that convey storm water to be

collected in a central underground water catchment basin. Fruit trees will be

planted in the four squares while the area in the vicinity of historic ruins is

designed as parterre gardens and lawns for festive events such as marriages and

other celebrations, thus adapting a heritage landscape to contemporary

recreational uses (figure 11). Musa Bagh Memorial Park will encourage heritage

tourism and, more importantly, become a precedent in restoring the river

ecology.

Figure 11 – Musa Bagh restoration plan